CREATING MY CARE RECORD

Co-DESIGNING CARE RECORDS WITH CARE EXPERIENCED PEOPLE

InTRODUCTION

Figure 1: Visual representation of what we mean by care records

Every person who has been in care has a care record. The record is used to record information about what has happened in their life while they are in care.

We are working with care experienced people to understand:

How would a care experienced person want to access and use the information in their care record?

How would they want to record their thoughts and feelings?

How would they share it and protect it?

We are also engaging with professionals who create and use care records to understand current record keeping practices and identify opportunities for new forms of care records that are designed around the needs of care experienced people.

Through this process we aim to iteratively codesign and develop new forms of care records, creating proof-of-concept prototypes and technical architecture that can integrate data from disparate systems to flow.

BACKGROUND

The Independent Care Review (ICR) found that current approaches to record keeping are designed around service needs and can be alienating or even traumatic for people in care. Data is held in many systems, by many organisations and services. Current record keeping practices allow the voice of the professional to dominate over the voice of the child. This may lead to decisions made on the child’s behalf which go against their wishes.

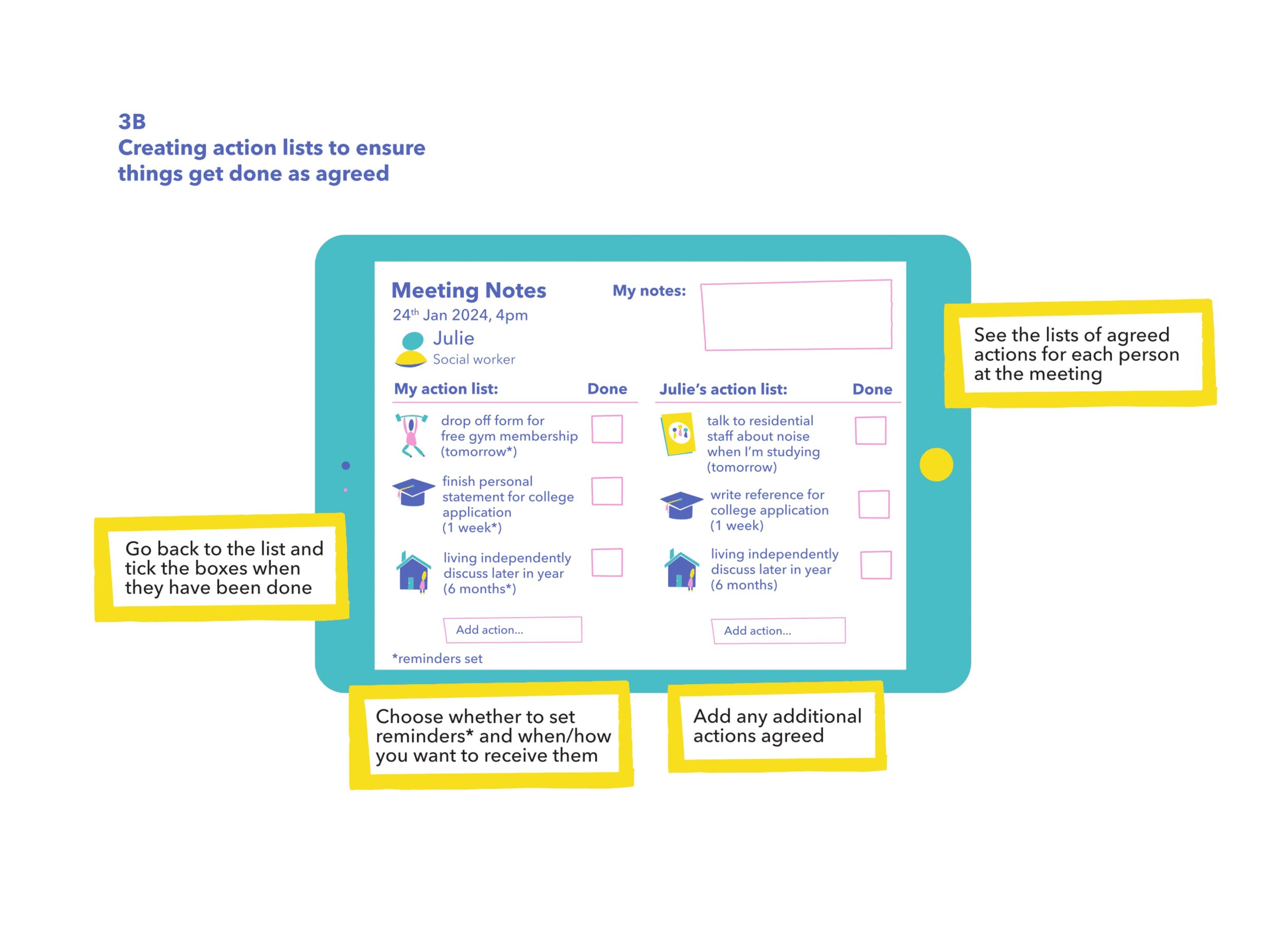

Previous engagement with people in care found that they want to feel respected by professionals and be able to contribute their own viewpoints to their care records. They should be able to participate in creating their records and incorporate creative and personal data as they wish. However, there are concerns with the security and longevity of independent apps designed for this purpose. They want to be aware of their rights and be supported in exercising them, particularly where it relates to the sharing of their data. They should be given the means to easily raise queries or concerns to professionals. People in care want to use their records to remain connected to their past and should be given the access and tools for them to do so. As care records often contain complex and distressing aspects of the person’s life story, it is integral that person-centred support should be available when they access their record.

This project builds on previous work done during the Independent Care Review (ICR) with the Digital Health & Care Innovation Centre (DHI) to explore co-produced care records that give ownership to and reduce stigma for young people. The project, funded by STV Appeal through the Corra Foundation, aims to research and prototype ideas for young people to tell their story in a way that is empowering for them and gives valuable insight to the organisations and services supporting them, using a “learn by doing” approach.

The project team is led by Heather Coady, Engagement Lead, and Chaloner Chute, Chief Technology Officer at the DHI. The Participatory Design process is led by design researchers from DHI / The Glasgow School of Art.

APPROACH

PARTICIPATORY DESIGN WITH CARE EXPERIENCED PEOPLE

Participatory Design approaches are based on a process of mutual learning between researchers and participants with lived experience of the challenge being explored. Designers seek to understand the lived experience of participants, and their desired future ways of living and working, while participants with lived experience are supported to share their experiences and aims, while learning about how technology can help to achieve this. Prototyping with participants with lived experience enables them to guide the design of any new technologies, without requiring them to have knowledge or skills in design and technology.

Our approach draws on an understanding of trauma-responsive design. This area of design research uses principles which have been developed for professionals working with people who have experienced trauma. This allows us to understand not only the principles that may inform the prototype design, but also gives us a framework for shaping the design of research activities.

Engagement

In parallel, we are focused on maintaining and growing relationships with relevant stakeholders with a view to ensuring a good level of support and buy-in to whatever might be developed. This engagement work has developed a strong and growing group of collaborators from across multiple disciplines and agencies all committed to and enthused by the project aims and approach. A selection of these collaborators sit on our Strategic Steering Group, which focuses on the ‘big picture strategic alignment and making sure we bring people along with us as we attempt to shift things using the project as a vehicle towards change. This group are helping to interpret and communicate our project aims, ongoing learning and outcomes to their respective organisations and networks and identifying possible implications and links to other changes happening across the wider system of care. We also have a Expert Advisory Group, who use their expert knowledge of the context to shape plans for Participatory Design engagements and ensure they are appropriate an sensitive to the needs of young people and those who support them. This group also provides validation and further analysis of the insights generated through Participatory Design activities and are guiding the translation of these findings into prototypes and proof of concept simulations.

TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENT

In close collaboration with Aberdeen City Council, we are developing a technical proof of concept which interfaces with council systems. Our proposed infrastructure for a person-centred approach is to store the young person’s information in a personal data store (PDS). The data from the PDS could then be displayed in one view to the young person (for example, in an app), but could also be used to keep council systems up to date. This ensures that young people have control over their information but that it can still be shared with professionals.

Figure 2: Overview of the different stages of the project, discussed in detail below.

SCOPING & framing

The question of person-centred care records is one which has already been researched in Scotland as part of the Independent Care Review (ICR) and overseas. Many of the stakeholders on this project had participated in the ICR and brought learnings from that work. Some of the stakeholders were also care experienced themselves. Because care experienced young people are such a heavily researched group, we wanted to ensure that we were not doing any unnecessary research by going over old ground. We began the project with a mini literature review of previous work along with professional scoping interviews, which gave us a good understanding of what had been done before.

trauma-informed Principles

We were keen to ensure that every aspect of the project was based on principles of human rights and that we were taking a trauma-informed approach. At the start of the project, we did a workshop with stakeholders based on Chayn’s principles of trauma-informed design. Using the principles, we asked stakeholders to brainstorm around how they would like to see these manifested in the work, and what questions they thought the project should answer. This activity ensured that the direction of the project was being informed by these values, and also helped us as researchers understand stakeholders’ concerns and expectations.

Framing the engagements

Figure 3: Scoping framed the challenge along a timeline in terms of how to: support sense-making of the past, record conversations with the young person and support decisions about the future.

At the heart of the challenge is how the voice of the young person can be captured in the care record, and how different kinds of conversations can be supported by the record. We identified potential uses for the care record, which map onto a temporal structure of past, present, and future (see adjacent image).

The record of the past relates to using care records to support conversations that help the young person make-sense of past events (including recent past), and how it can tell the young person’s story in a way that supports relationship building conversations (listen and connect) with new people.

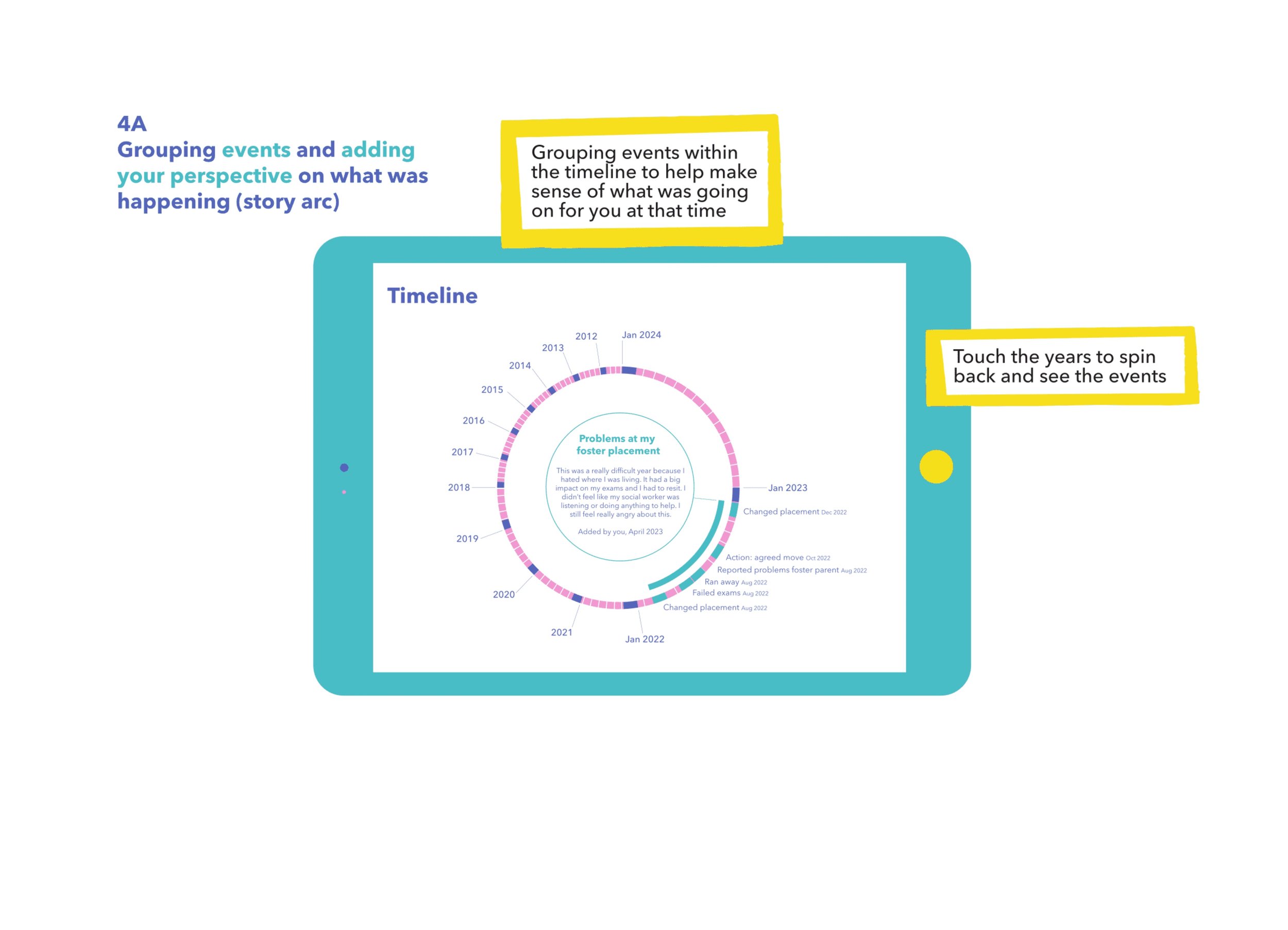

The record of the present requires us to consider how conversations are recorded in the moment and build to form a rich record of the past. This includes the recording of photos, certificates, and other achievements, which can be preserved and looked back on in later life. It requires us to understand current record keeping practices of professionals, and if/how the young person currently records and shares their views. Any new tools for record keeping need to be designed to support conversations, therefore we need to understand what makes a good conversation and how tools can enhance these interactions.

The record of the future creates a space to support decision-making conversations, in discussing different possible options and how these relate to the young person’s hopes for the future. It also supports conversations that enable planning for near future events. It provides an opportunity to explore how new technologies (i.e. verified attributes currently being developed by the Digital Identity team) that empower the young person to use their story (i.e. record of the past) to more easily see and access support they are entitled to without needing to disclose any personal information.

INTERVIEWS WITH CARE EXPERIENCED PEOPLE

In the next stage of the work, we recruited three care experienced young people through Who Cares? Scotland for in-depth interviews. At the interviews, we asked them tell us a little bit about themselves and their experiences of care, their thoughts about their care record, and how they preferred to communicate and share information. The engagements were planned in conjunction with Who Cares? Scotland and our Expert Advisory Group to ensure that we were taking a trauma-informed approach which was supportive of the young people involved, and participants also received compensation for their time.

The names shown on the interview maps below are pseudonyms.

FOCUS GROUPS WITH MULTIDISCIPLINARY PROFESSIONALS

We also carried out a two focus groups with 11 professionals across a wide range of roles, all of which were involved in supporting young people. At the focus group, we used a persona of a care experienced young person to discuss current record-keeping practices and how professionals thought these might be improved in future.

Figure 7: Through multidisciplinary focus groups with professionals, we learned about their current record keeping practices and what they thought could be improved.

ANALYSIS, TRANSLATION & PARALLEL PROTOTYPING

Through the insights from the interviews and focus group, we identified four key concepts which could be explored further through digital prototyping:

Joined-up services: Making care more supportive through improvements to technical infrastructure which can improve communication, automate tasks, and show young people the menu of services and benefits which are available to them.

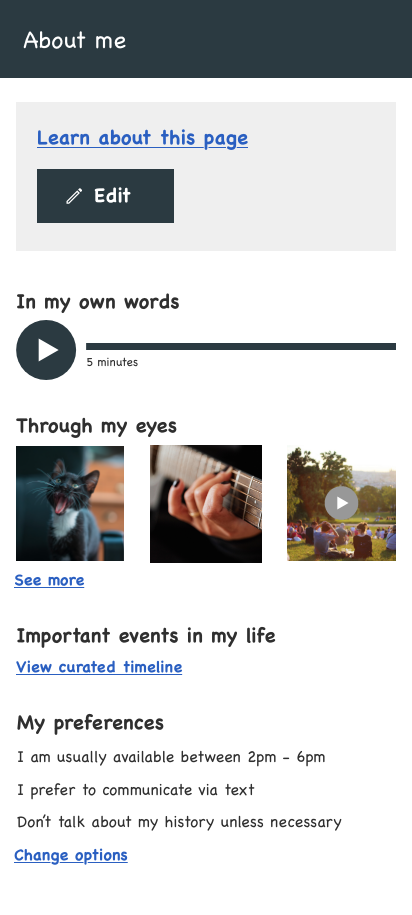

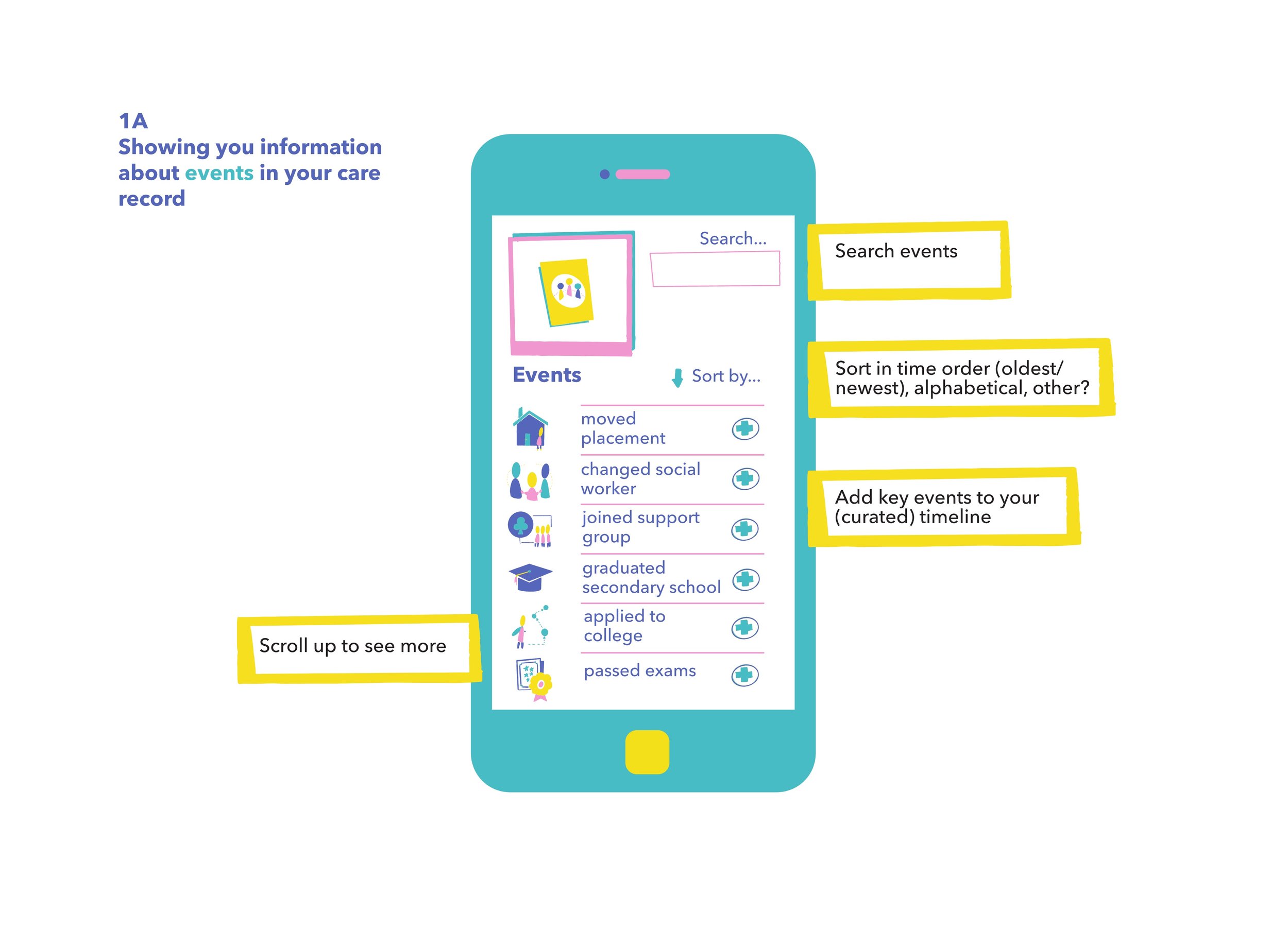

Timeline: Being able to easily search and browse through a record of past events, and also see a plan for the future.

Co-authored records: Implementing ways for young people to include their own voice in their care record and participate more equitably alongside professionals in planning and decision making.

Controlling access: Giving young people control over how their information is being viewed and shared with others.

Using the concepts, we iteratively developed digital prototypes for how care records might work in future. The prototypes were first built up through sketching and conceptual ideation, and then creating more high-fidelity prototypes in Adobe XD. This process allowed us to think through some of the technical functionality and user interactions. The higher-fidelity prototypes were also used to build confidence with stakeholders and help them envision how a new care record might look.

We then went back and created more simplified, lower-fidelity versions of the prototypes to use in the follow-up engagements. These lower-fidelity versions matched the original look and feel of the interview maps, and were designed to be more accessible and easier to understand for participants.

Each version of the prototype was used for a different purpose within the project, and also helped us to explore different ideas.

validation of concepts

Working again with Who Cares? Scotland, we are now in the midst of validating the concepts which we developed through the analysis and prototyping by carrying out:

Follow-up interviews with each of our original interviewees

Workshops with care experienced people separated into two groups: over 16 and under 16

In each of these activities, participants are shown and asked to give feedback on the prototypes which we created. They are then asked to create scenarios which demonstrate how the prototypes might be used. This helps us to understand the context in which the prototypes might be used, and any barriers to use which care experienced young people might have.

NEXT STEPS

We are working to build momentum and realise the future vision through national engagement and collaboration. This will involve a period of validation with other regions to understand if what we have found and developed in Midlothian and Moray has wider applicability. Early conversations show excitement and appetite for this kind of transformational change to better meet the needs and aspirations of citizens.

Further Information

For more information about this project please contact:

Heather Coady, heather@coady.org.uk

Marissa Cummings, M.Cummings@gsa.ac.uk

Gemma Teal, G.Teal@gsa.ac.uk

Chaloner Chute, chalonerchute@dhi-scotland.com